Achilles Tendinitis Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment

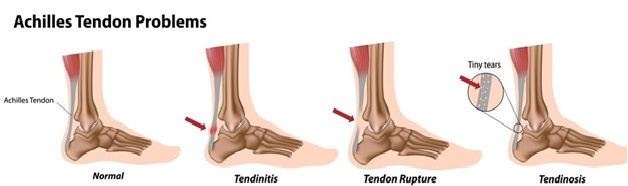

What Is Achilles Tendinitis

Achilles tendinitis is a common condition that causes pain along the back of the leg near the heel. It is an overuse injury of the Achilles tendon, the band of tissue that connects calf muscles at the back of the lower leg to your heel bone.

Achilles tendinitis most commonly occurs in runners who have suddenly increased the intensity or duration of their runs. It’s also common in middle-aged people who play sports, such as tennis or basketball.

Causes Of Achilles Tendinitis

Achilles tendinitis is not related to any specific injury. It results from a repetitive stress to the tendon. The following factors can increase the probability of acquiring Achilles tendinitis:

- Sudden increase in the amount or intensity of exercise activity—for example, increasing the distance you run every day by a few miles without giving your body a chance to adjust to the new distance

- Tight calf muscles—Having tight calf muscles and suddenly starting an aggressive exercise program can put extra stress on the Achilles tendon

- Bone spur—Extra bone growth where the Achilles tendon attaches to the heel bone can rub against the tendon and cause pain.

Symptoms Of Achilles Tendinitis

Common symptoms of Achilles tendinitis include:

- Pain and stiffness along the Achilles tendon in the morning

- Pain along the tendon or back of the heel that worsens with activity

- Severe pain the day after exercising

- Thickening of the tendon

- Bone spur (insertional tendinitis)

- Swelling that is present all the time and gets worse throughout the day with activity

- Stressful situations are often accompanied by Achilles tendinitis

- Burning sensation in the leg in question

Diagnosis Of Achilles Tendinitis

The following tests are used to diagnose Achilles tendinitis:

- X-rays

While X-rays can’t visualize soft tissues such as tendons, they may help rule out other conditions that can cause similar symptoms.

- Ultrasound

It can also produce real-time images of the Achilles tendon in motion, and color-Doppler ultrasound can evaluate blood flow around the tendon.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Using radio waves and a very strong magnet, MRI machines can produce very detailed images of the Achilles tendon.

Treatment Of Achilles Tendinitis

The treatment for Achilles tendinitis can be broadly categorized into surgical and non surgical treatment, depending upon the intensity of the injury.

- Non-surgical treatment

- Rest

- Placing an ice over the affected area

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication including ibuprofen and naproxen which reduce pain and swelling

- Exercise including calf stretch

- Physical therapy

- Cortisone injection

- Surgical treatment

- Gastrocnemius recession

- Debridement and repair

By : Natural Health News