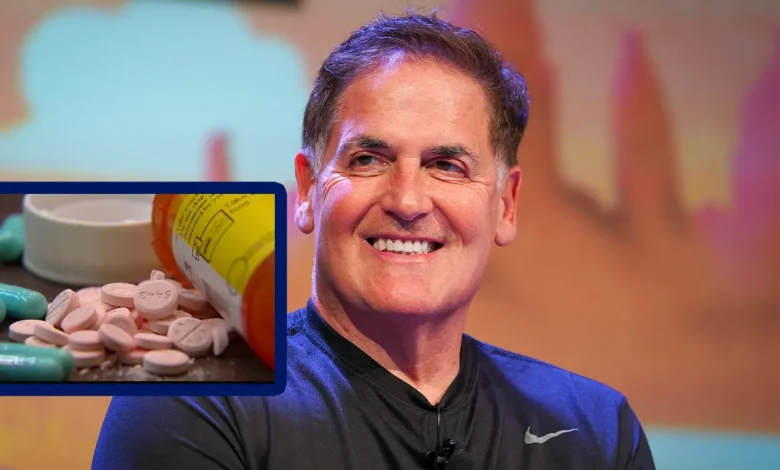

Mark Cuban’s Bold Claims on PBMs and Drug Prices — Fact or Fiction?

Mark Cuban has become one of the most visible private-sector critics of how Americans pay for prescription drugs. Through speeches, interviews and his Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company (MCCPDC), he argues that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) — the middlemen who negotiate drug prices for insurers and employers — are a key reason U.S. drug prices are sky-high, and that cutting out opaque PBM practices and adding pricing transparency can dramatically lower costs. Those are attention-grabbing claims. But are they accurate — or oversimplified?

This article walks through what PBMs do, summarizes Cuban’s main arguments, weighs the evidence for and against them, examines what his Cost-Plus model actually changes, and explains what broader policy or market fixes would be needed to produce systemic price reductions. Where relevant I cite recent reporting and research so you can see which claims stand on strong evidence and which are still debated.

Quick primer: what are PBMs and why they matter

Pharmacy Benefit Managers are intermediaries hired by insurers, employer plans and sometimes government programs to manage prescription drug benefits. Their functions include negotiating discounts and rebates with drug makers, creating formularies (which drugs are favored), processing pharmacy claims and setting patient cost-sharing tiers. Over the last two decades PBMs became highly consolidated — three large PBMs now process the majority of U.S. prescriptions — which increases their leverage with both manufacturers and pharmacies.

PBMs argue they save money by negotiating rebates and steering patients to less costly alternatives. Critics counter that PBM business models are opaque: rebates and spread pricing can lead to situations where the PBM or its affiliated entities benefit more than the insurer or patient, and where list prices and out-of-pocket costs diverge from the “net” prices PBMs negotiate. Federal and congressional reports in recent years have documented both the power of PBMs and the opacity of many of their practices.

What Mark Cuban says (the claims, in plain language)

Cuban’s public argument has a few repeating themes:

- PBMs inflate prices through opaque fees, rebates and favoritism, so they fail to pass real savings to consumers.

- Cutting out PBMs (or at least forcing transparency and simpler pricing) can dramatically lower what patients pay.

- His Cost-Plus model — listing a small, fixed markup over drug cost plus a transparent fee — proves the point: many drugs can be sold far cheaper than what consumers often pay.

Those claims blend empirical observations (PBMs are opaque, and many consumers pay high prices) with an implied policy prescription (greater transparency and simpler pricing will solve the problem).

What evidence supports Cuban’s central points?

- PBMs are powerful and opaque. Multiple government and independent reports document concentration among PBMs and opaque rebate/contracting practices that make it hard for outside parties to see the true flow of money. That opacity creates opportunities for misaligned incentives.

- Simple cost-plus pricing can beat typical consumer prices on many generics. Independent comparisons and academic case studies have found that for a broad set of off-patent generics, MCCPDC prices are often lower than typical retail prices or coupon prices online — especially for patients without insurance or whose insurance has high cost-sharing for specific drugs. Some peer-reviewed evaluations and observational analyses find meaningful savings on selected medicines when using cost-plus models.

- There are examples where rebate-driven systems favor higher list prices that then get offset by rebates — which can leave some patients paying more at the pharmacy counter. Studies and reporting show that list price dynamics and rebate flows can create odd outcomes, such as a high-list-price drug receiving big rebates to be on formularies while lower list-price alternatives are disadvantaged.

Taken together, those points back up Cuban’s broad observation: the current middleman system can create outsized rents and obscure the true cost of drugs.

Where Cuban’s argument is incomplete or contested

- Scale and scope: Cost-plus works for many generics, but not for everything. Cost-plus is most straightforward for widely available off-patent generics where manufacturing cost is low and markets are competitive. But newer brand drugs, biologics, complex generics and specialty medicines involve high R&D or manufacturing expenses, limited competition and supply-chain constraints — areas where cost-plus alone cannot magically produce the same percentage reductions. Analyses caution that Cost-Plus’s model addresses a slice of the market, not the entire $700+ billion drug ecosystem.

- Rebates can produce lower net costs for payers even if they don’t help patients at the counter. PBMs sometimes secure rebates that lower the insurer’s net spending; that isn’t the same as lowering the price faced by a patient at a pharmacy or for a cash purchase. So while rebates may create perverse incentives, they can also reduce overall system costs depending on how savings are shared — which varies by contract. Policymakers and analysts disagree on how harmful rebates are and how best to reform them.

- PBMs perform functions beyond simple price negotiation. They manage utilization (step therapy, prior authorization), pharmacy networks, mail-order distribution, and sometimes drug adherence programs. Eliminating PBMs without replacing those functions could have unintended consequences for prescribing patterns, medication access and program integrity. The debate is whether those functions can be provided more transparently and cheaply, not whether PBMs add any value at all.

- Evidence for system-wide savings through transparency alone is limited. Cuban often emphasizes transparency as the linchpin. Transparency helps — it’s extremely hard to critique or reform what you can’t see — but several experts say transparency is necessary, not sufficient. Structural changes (competition policy, rebate reform, changes in benefit design, importation policies, increased generic manufacturing resilience) are also likely needed to shift prices across the market.

How much has Cost-Plus actually moved the needle?

MCCPDC has delivered lower prices for many generics and simple molecules, and its public pricing helped highlight how much markup can exist in the system. There are peer-reviewed and independent analyses showing MCCPDC’s prices beat many alternatives for selected drugs — particularly generics and off-patent items purchased with cash or through limited benefit coverage. But when researchers model system-level savings — including specialty drugs, public programs like Medicare Part B/Part D, and the reality of contractual networks — MCCPDC-style models alone do not, on their own, eliminate the fundamental forces that drive high prices for brand and specialty drugs. In short: Cost-Plus is real and useful, but it’s a partial solution.

Real-world constraints and policy context

- Consolidation matters. The FTC and other regulators have flagged how PBM consolidation and vertical integration (PBMs owning mail-order pharmacies or being part of insurer conglomerates) can skew incentives. Breaking up or regulating those structures would be a heavy lift politically and legally — but is central to any broad fix.

- Rebate reform is politically contentious. Some proposals aim to ban rebates or require pass-throughs to consumers, while others suggest banning spread pricing or forcing PBMs to be more transparent. Each reform affects different stakeholders in different ways — some might reduce list prices, others shift costs into premiums, and some risk reducing manufacturer willingness to offer discounts. Evidence on the net effects is mixed.

- Supply chain resilience for generics matters. Lower prices without attention to manufacturing and sourcing can reduce the number of suppliers and cause shortages. Several reports have emphasized that ultra-low generic prices have pushed production offshore and increased supply fragility — a dynamic critics warn against if not managed with industrial policy.

Verdict: fact, fiction, or nuance?

- Fact: PBMs are powerful, their business practices are often opaque, and that opacity has allowed behaviors that sometimes misalign incentives between patients, plans and manufacturers. Greater transparency and alternative models can produce real savings for many commonly used generics.

- Fiction (if stated too broadly): The idea that eliminating PBMs or simply copying Cost-Plus across the entire market will by itself produce sweeping, economy-wide reductions for all drugs — including new specialty biologics and oncology drugs — overstates what a single private company can achieve. Many high-cost drugs are driven by R&D, limited competition, patent law, and complex manufacturing — issues outside the PBM box.

- Nuance: Cuban’s model proves an important point: greater price transparency and simpler markups can and do lower costs for many medicines. But to transform total drug spending sustainably requires a suite of reforms: market competition, supply-chain policy, smart rebate/benefit design reform, and, where appropriate, regulatory action on consolidation.

What should consumers and policymakers take away?

For consumers: if you’re paying cash or facing a high co-pay, try cost-comparison tools and alternatives (including transparent cost-plus pharmacies) — you may save money on generics. For employers and plan sponsors: insist on transparency in PBM contracts and examine whether rebate flows and spread pricing are actually reducing net costs for your plan.

For policymakers: Cuban’s spotlight on transparency is useful; so are the accompanying data showing that a few structural features of the system (market concentration, opaque contracting, and certain rebate dynamics) warrant closer scrutiny. But the right policy package will likely include multiple levers — not just forcing PBMs out, but ensuring fair competition, protecting supply chains, and designing patient-friendly benefit rules so that rebates and discounts are shared with patients at the point of sale.

Final thought

Mark Cuban’s rhetoric helped push a necessary public conversation into the open. His Cost-Plus experiment is valuable proof-of-concept: pricing can be simpler and, for many drugs, lower. But turning that experiment into an economy-wide solution demands both humility and policy muscle. The problem of high U.S. drug prices is multi-headed; no single billionaire, company or law will be a silver bullet. We’re better off treating Cuban’s intervention as an important lever in a larger toolbox that must include antitrust enforcement, smarter benefit design, targeted industrial policy and clearer rules about how savings are passed to patients.