Brain-Eating Amoeba Kills Patient in South Carolina: Deadly Waters?

Opening the Depths of Horror

In mid-July 2025, the tranquil waters of Lake Murray in South Carolina became the scene of an unthinkable tragedy. A pediatric patient, believed to have been exposed to Naegleria fowleri—the notorious “brain-eating amoeba”—died of primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), a disease so rare that only around 10 cases emerge annually in the entire United States, yet so lethal it claims nearly all who are infected.

The South Carolina Department of Public Health confirmed that exposure occurred during the week of July 7, 2025, most likely at Lake Murray, though officials remain cautious: an official statement noted they “cannot be completely certain”. Prisma Health Children’s Hospital–Midlands in Columbia, where the patient was treated, confirmed the adult or pediatric patient’s death today, though they declined to provide further details.

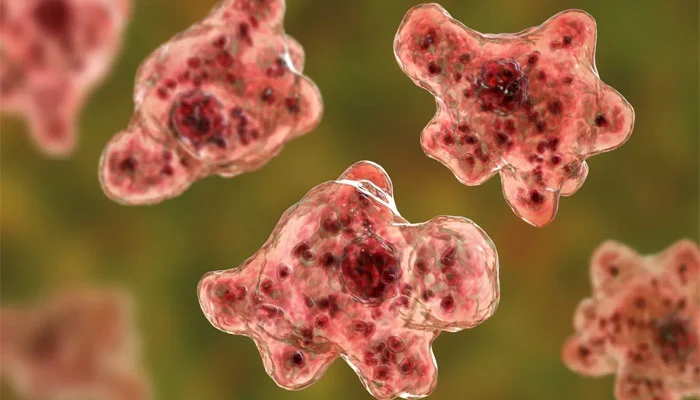

A Rare Invader: Naegleria fowleri

What Is Naegleria fowleri?

This free-living amoeba thrives in warm freshwater environments—lakes, rivers, hot springs, even poorly maintained pools—especially during summer months when temperatures approach 80–115 °F (27–46 °C). It lurks in sediments and loves heat; it even proliferates near warm-water discharge sites.

Most of the time, N. fowleri is harmless; it normally feeds on bacteria. But danger strikes when contaminated water enters the body through the nose—such as during diving or submersion. From there, the amoeba travels along the olfactory nerve, burrows through the cribriform plate, and invades the brain.

What Happens Inside the Brain?

Once inside, the trophozoites destroy nervous tissue, causing intense inflammation and swelling. The resulting condition—primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM)—combines meningitis and encephalitis. Symptoms emerge swiftly: headaches, fever, stiff neck, confusion, nausea, hallucinations, seizures; death typically follows within 1–18 days, with the median being 5 days post symptom onset.

Though PAM is frighteningly fatal—over 97% mortality rate since the 1960s—a mere 167 cases have been identified in the U.S. between 1962 and 2024.

South Carolina’s First Case Since 2016

This recent infection marks South Carolina’s first confirmed PAM case since 2016, and one of only a handful in the state since 2010. State Epidemiologist Dr. Linda Bell emphasized it does not constitute a public health emergency, noting:

“Recreational water activities for the general public are actually quite safe. About 10 cases per year in the United States… the fact that this is so rare … tells us warm bodies of water do not pose a significant threat.”

While terrifying, PAM remains an extremely rare occurrence relative to the millions of safe freshwater visits each year.

Exposure at Lake Murray

This case’s suspected site of infection, Lake Murray, lies just west of Columbia. Officials believe contamination occurred in early July—during a hot stretch when water temperatures were optimal for N. fowleri growth.

South Carolina Health Department does not mandate water testing for Naegleria fowleri. Instead, swimmers are presumed at risk during warm weather and advised to take preventive measures.

Medical Response and Treatment

Symptoms and Onset

- Incubation: 1–12 days after nasal exposure

- Initial Signs: headache, fever, nausea, vomiting, stiff neck

- Progression: confusion, seizure-like activity, hallucinations, loss of balance

Once suspected, diagnosis hinges on analyzing cerebrospinal fluid under a microscope to detect trophozoites.

Treatment Challenges

Standard treatment involves:

- Amphotericin B — long the mainstay, but historically ineffective for PAM, with most still dying.

- Emerging therapies include miltefosine, antifungal agents (voriconazole, posaconazole, fluconazole), steroids (to reduce brain inflammation), and targeted cooling strategies.

A few rare survivors suggest a combination of early recognition, aggressive and multi-modal treatment may offer hope—but outcomes remain widely unpredictable.

The Human Toll & Awareness Driving Advocacy

Though officials release few personal details, the death profoundly impacts families. Jeremy Lewis, whose 7‑year‑old son Kyle died from PAM nearly 15 years ago, founded the Kyle Lewis Amoeba Awareness Foundation. In a WACH interview, he said:

“Losing a child is awful but when you lose them this way, it is horrible… If you listen to professionals, it’s rare. It may be rare to you, but it’s not for me.”

The foundation actively educates families and healthcare professionals about the dangers of nasal exposure to contaminated water.

Prevention: Simple Yet Critical

Given the grim prognosis once infection takes hold, prevention is key:

- Avoid water entering the nose: hold your nose or use nose clips when submerged.

- Keep your head above water in warm freshwater bodies and hot springs.

- Don’t stir up sediment at the bottom of shallow waters—amoebae concentrate there.

- Use boiled or distilled water for nasal rinsing, sinus irrigation, or ablutions.

These measures align with CDC recommendations and have been endorsed by South Carolina officials.

The Environmental Reality

Naegleria fowleri is not a new threat. It was characterized in the 1960s and has long been known to inhabit U.S. southern waters during warm seasons.

The amoeba exists in three forms—trophozoite (infective), cyst (dormant), and flagellate (transient). The cyst is resistant to harsh environments, but warm water triggers the trophozoite form that causes infection; the flagellate form can appear in cerebrospinal fluid.

Its presence in soil, pipes, tanks, and groundwater means it’s hard to eliminate completely. Agencies sporadically test for it, but no widespread monitoring or remediation programs exist.

Public Health Policy Gaps

South Carolina’s approach—advisory-based prevention—reflects national norms. Since cases are rare, governments do not mandate testing or posting widespread warnings: the DPH maintains Naegleria fowleri infection isn’t a reportable condition and lacks large-scale countermeasures.

Critics argue that improved environmental surveillance—especially during summer months—could help boards of health issue timely alerts. Others counter that false alarms, economic impact, and public panic could undermine recreational safety and natural resource-based economies.

Research: A Glimmer of Hope from the Lab

Investigators are searching for therapeutic breakthroughs. Clemson University’s Eukaryotic Pathogens Center (EPIC) is testing targeted drugs to counter N. fowleri infection. Among promising avenues is the use of an enzyme called HEX, originally used in brain cancer, which when tested in animals delayed disease progress—though it stopped short of completely eradicating the amoeba.

These efforts, while preliminary, illustrate dedication toward reducing mortality in future PAM cases.

What Comes Next?

For the public, the messaging is consistent: warm freshwater carries a risk, but swimming is overwhelmingly safe if precautionary steps are taken.

For health authorities: Greater surveillance in high-risk waters, improved public education campaigns, and more rapid treatment protocols for patients showing early PAM symptoms—like meningitis—could shave critical hours from diagnosis.

In labs: continued funding and collaboration is vital to push existing therapies forward and identify new anti-amoebic agents capable of penetrating the brain.

Conclusion

What happened in South Carolina is more than a statistical anomaly—it’s a sobering reminder of nature’s hidden dangers. In just a single moment at Lake Murray’s waters, the fragile barrier between everyday life and a rare but fatal neurological assault was breached.

Yet, amid this horror, a narrative of resilience emerges. Health professionals push for awareness and vigilance; families like the Lewis’s advocate tirelessly; scientists work toward hopeful treatments.

Every swimmer, parent, and health leader can now benefit from this knowledge. By holding your nose, avoiding warm, shallow waters, and staying informed, you act as the frontline defense against an enemy so small yet so devastating