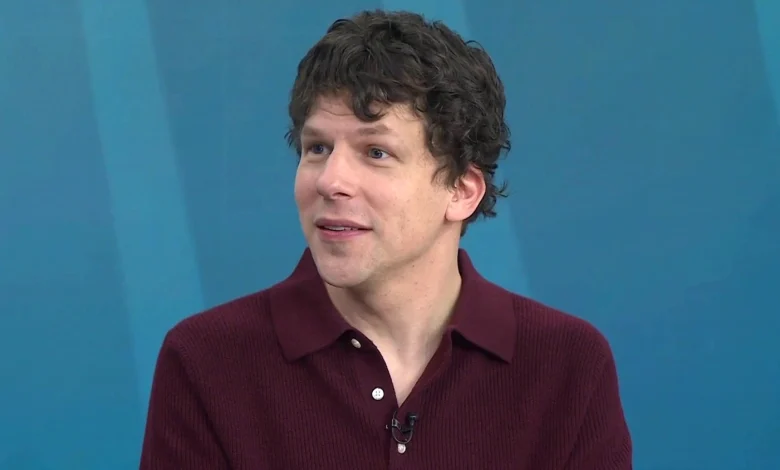

Jesse Eisenberg’s Brave Decision to Donate His Kidney to a Stranger

When we think of acts of generous self-sacrifice, they often feel distant: big ideas for someone else’s life, sometimes removed from our own everyday context. Yet the recent announcement by actor Jesse Eisenberg that he will donate one of his kidneys to a complete stranger brings this kind of altruism into sharp, personal focus. It’s a story worthy of attention—not just because of his celebrity status, but because of the values and systems it touches: bodily autonomy, the ethics of giving, the logistics of organ donation, and what it means to help when you don’t have a prior relationship with the recipient.

1. Who is Jesse Eisenberg — and what led him here?

Jesse Eisenberg rose to prominence in film through several memorable roles: the socially awkward Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network, the oddball hero in Zombieland, and appearances in a variety of indie and mainstream films. Over time, aside from acting, he has engaged in philanthropy and public initiatives (though perhaps less loudly than some celebrity peers).

According to his own words, he has long been a blood donor (“I just have so much blood in me … I feel like I should spill it”). That desire to “give” in a small way seems to have scaled up into what he describes as a “no-brainer” decision to donate a kidney to someone he doesn’t know.

What’s compelling is the evolution: from regular blood donations (fairly common and low-risk) to a far larger gesture of living organ donation. It suggests a mindset not limited to symbolic giving, but real, physically impactful action.

2. The Donation: Details, Process & Significance

What’s being done

Eisenberg has publicly revealed that he will undergo a living non-directed (also called “altruistic”) kidney donation scheduled for mid-December (in the time of his announcement). He told the National Kidney Foundation voucher program means his family would be prioritized in the future if someone in his family needs a transplant.

He said, “I’m actually donating my kidney in six weeks. I really am.” and described his decision as “a no-brainer.”

What’s an altruistic/non-directed donation

In living kidney donation there are typically two types: directed (you donate to a specific person you know) and non-directed (you donate to someone you don’t know). Eisenberg’s is the latter. For non-directed donations:

- The donor is matched medically with a recipient in need.

- Often this donation starts a “chain” of matches: if Donor A gives to Recipient B, B’s intended donor (if incompatible) can give to someone else, creating a domino effect. Eisenberg explained this process: “Let’s say person X needs a kidney… their child or whoever was going to donate… is not a match, but somehow I am.”

- The donor must pass a series of rigorous medical checks, psychological evaluation, and understand the risks and recovery. Eisenberg noted he went to the hospital “the next day” for a battery of tests.

Risk vs Benefit

Eisenberg claimed the procedure is “essentially risk-free and so needed.” While “risk-free” may be a simplification (no medical procedure is entirely without risk), living kidney donation has become relatively safe in the developed world, with many donors returning to normal activities within 2–4 weeks.

The benefit? One person (or potentially many, via a chain) gets a second chance at life, often avoiding years of dialysis and dramatically improved quality of life.

Why this decision matters

- It highlights extreme generosity: donating a major organ to someone you don’t know is rare.

- It brings attention to the shortage of kidneys and the need for living donors.

- Because Eisenberg is a public figure, his action may amplify awareness and encourage others.

- He also addresses common concerns: he enrolled a family-voucher program so his family is not “left behind” if someone in his family later needs a kidney. This shows thoughtfulness about future contingencies.

3. Broader Context: Organ Donation and Altruistic Giving

Kidney shortage

Worldwide (and particularly in the U.S.), there’s a significant mismatch between the number of people needing kidney transplants and the number of available organs. According to one report, around 90,000 people were waiting for a kidney transplant in the U.S. at one point. Living donation is one of the most effective ways to increase supply.

Benefits of living donation

- For the recipient: shorter waiting times, better outcomes, often a healthier donor kidney.

- For the donor: though a sacrifice, many report no serious long-term health issues; the remaining kidney typically compensates.

- For the system: Non-directed donors (like Eisenberg) can catalyze donation chains, creating multiple transplants from one initial act.

Ethical and social dimensions

- Informed consent: Donors must be fully aware of risks, recovery, possible complications.

- Not coerced: The decision must be free of coercion or financial incentive (commercial organ donation is illegal in many jurisdictions).

- Family implications: Many potential donors worry about their own future health or leaving their family vulnerable. The voucher programs address some of these fears.

- Recognition vs humility: High-profile donors (especially celebrities) risk being perceived as seeking publicity rather than pure altruism—but this also can raise positive awareness.

4. What This Decision Says: Values, Celebrity Influence & Public Awareness

On values

Eisenberg’s decision suggests a value system centered on practical help rather than symbolic gestures. One might donate money or speak out; he is offering part of his body to help another. It suggests a level of personal risk and commitment beyond typical celebrity philanthropy.

By calling it a “no-brainer,” he normalizes the idea: if you’re healthy, donating a kidney (or considering it) can be a straightforward act of compassion. That message is powerful.

On celebrity influence

Celebrities have a mixed reputation when it comes to philanthropy—some rightly criticized for virtue-signalling, others for meaningful commitment. When a celebrity does something concrete (especially medically significant), it can:

- Influence public discourse (people think “If he can do it, maybe I can too”).

- Improve public understanding of the donation process.

- Reduce stigma or fear around donation (many people fear the surgery, loss of a kidney, etc.).

In Eisenberg’s case, his transparency about why he is doing it (“I love donating blood… one thing led to another”) and how (voucher program for family protection, chain matching) helps demystify the process.

On public awareness

- Many people don’t know what “altruistic donation” or “non-directed living organ donation” means; his explanation helps.

- By openly discussing his timeline, motivations, and preparations, he offers insight and may inspire others.

- It raises questions: “Could I do that? Should I think about it?” which is healthy for society.

5. Potential Criticisms or Caveats

No decision is entirely without nuance, and while Eisenberg’s feels deeply admirable, some caveats should be acknowledged:

- Medical risks: While relatively safe, living kidney donation is still surgery. There’s recovery time (2-4 weeks in optimal cases) and potential for complications (infection, incisional pain, long-term kidney health concerns).

- Privilege and resources: A healthy, financially stable celebrity may have advantages (access to top medical care, ability to take time off, fewer financial pressures). In many parts of the world, potential donors may face economic hardship during recovery. That doesn’t diminish Eisenberg’s gesture, but it frames it in a context of privilege.

- Celebrity optics: As mentioned, some may wonder if this is partly a publicity move (since he happened to be promoting a film). But his explanation and preparations suggest genuine intent.

- Family and long-term implications: Though he enrolled his family in a voucher program, potential donors must consider their family situation, possible future health issues, and whether donating is the right choice for them.

- Global perspective: The U.S. organ donation system may have certain protections and benefits; in less-resourced settings the risk/benefit calculation might differ.

6. What We Can Learn — And What We Can Do

From Eisenberg’s decision, several take-aways emerge:

- Generosity can scale: If you donate blood regularly, maybe think about whether you could donate an organ (if medically suitable). He shows that a small regular habit (blood donation) can lead to thinking about a bigger contribution.

- Education matters: He explained the voucher system and chain donation mechanism. Many don’t know these exist—and knowing might reduce fear or hesitation.

- Health and preparation are key: One must be medically healthy, well-informed, and have support. He made it clear he went through tests and made preparations for his family’s future.

- Visibility helps: When someone in the public eye does something concrete, it shines a spotlight. That can create ripple effects—others may ask “Could I?” or “Should I?”

- Ethics of giving: We often focus on money, but giving part of yourself (your kidney) is one of the most profound gifts. It reminds us that generosity is not just financial.

- Normalizing altruism: By saying “it’s a no-brainer,” he normalizes organ donation to healthy people as something feasible. If a major actor can do it, perhaps many more can consider it.

Conclusion

Jesse Eisenberg’s decision to donate his kidney to a stranger stands out for multiple reasons: its scale, its altruistic nature, and its visibility. But beyond his fame, the story is fundamentally human: someone who is healthy, who already gives (blood), taking the next step to save or substantially improve another’s life—even when he doesn’t know them.

It reminds us of the power of giving without expectation, of generosity rooted in action rather than image. It also highlights the incredible network of medical care, ethical guidelines, and social values required to enable such a gift safely and meaningfully.

In a world where news is often of conflict or self-interest, this kind of announcement brings hope. Maybe more importantly, it sends the message: if you can help—especially when the cost to you is manageable and the benefit to someone else huge—why not?

Whether you’re inspired, curious, or moved, consider this: what is your next giving step? It doesn’t have to be as dramatic as donating a kidney—but it could be meaningful. Jesse Eisenberg’s act is a powerful prompt for all of us.